Hieroglyphs:

History, Politics and Pop Culture

Egyptian

Hieroglyph is a form of written language, developed approximately between 4000-3000

B.C. With the decrease in use due to cultural shifts, there has been a move

from the linguistics of the Ancient Egyptian language that hieroglyph

represented, a language which has not been used for hundreds of years, back to

the visual communication that hieroglyphs began as. Aside from being used for

activities such as children’s games or being used to research ancient Egyptian culture,

hieroglyph is no longer used. However, symbolically, hieroglyphs are now used

to represent ideas and to link the past with the modern. They have come to

represent a form of storytelling that can be seen in both North American pop

culture, and in the midst of Egyptian political strife.

The

term ‘hieroglyph’ was “given by the Greeks to the signs which they found carved

on the walls of the Egyptian temples and tombs, on statues and on coffins. It

means literally ‘sacred writing’” (Sewell, 2001, p. 95) . Development came

about over time, as there are indications that “…writing was an indigenous

development in Egypt, deriving from earlier displays of visible communication:

stelae, statuary, painting and rock art” (Silverman, 2011, p. 209) . The exact origins

of Egyptian hieroglyphs is unknown, but according to some scholars, there could

be a link to the development of a new state in North Africa, towards the end of

the 4th millennium BC, and the development of writing (Silverman,

2011, p. 203) .

According to Silverman (2011), historians have suggested that “…writing in

nearby Mesopotamia predated writing in Egypt...” and that it could have

“…served as a model for what eventually appeared in Egypt.” The idea that hieroglyphs were a form of

sacred writing, is not unfounded. Literacy was not widespread in Egypt and it

was used primarily by the religious and royal population. Used to decorate

tombs and temples, the text was used alongside imagery to communicate stories

about the gods and the kings and pharaohs, the people that were considered to

be as close to the gods as a human could be. Hieroglyphs were also used in

decoration, or to indicate specific uses for specific objects, and “…occasionally

function[ing] as part of relief decoration on early furniture, where they

simultaneously provided an amuletic message” (Silverman, 2011, p. 208) . Inscriptions on

vessels and jars made note of what they were created to hold, not unlike the

way we label the spices in a spice rack today.

Egyptian

hieroglyphs are a mix of symbols used to represent words known as ideograms, or

symbols, and phonetic or cursive writing, “…a result of writing with a rush pen

on papyrus” (Sewell, 2001, p. 96) and was used to

represent specific linguistic consonant and vowel sounds. Instead of using

syllabic symbol, such as the letters of the English alphabet, each ideogram

represented a single word or many ideas. The idea represented by a hieroglyph

was often unclear, being left to the reader to interpret the precise meaning.

This decipherment was also aided by the use of determinatives, such as “a pair

of walking legs…added to the end of verbs of motion” (Kemp, 2005,

p. x) ,

because the writing required “a constant shifting back and forth between symbol

and sound value…to form word shapes” (Kemp, 2005, p. x) .

The

use of both ideographic and phonetic writing led to the development of heratic

and demotic writing as “[d]uring its historic period, Egypt had two scripts,

cursive and hieroglyphic, and each was generally used on different media and

for different purposes.” (Silverman, 2011, p. 206) Both cursive and

hieroglyph “served as phonetic or ideographic components, but only hieroglyph

could occasionally retain that role and function simultaneously as an integral

element in a scene.” (Silverman, 2011, p. 207) Hieratic script was developed first, and over

time became a demotic script, relying more on phonetics, and less on symbol.

While there is still some relationship between the two, “it is very difficult

to recognize the original hieroglyphic forms, and which is also very difficult

to read” leaving demotic script “in common use from about the eighth century

B.C. until late Roman times.” (Sewell, 2001, p. 96) This did not mean

the hieratic script ceased to be used altogether, rather it became a

specialized language, used “...reserved for religious and ceremonial texts so

that eventually it was understood only by the priests and temple scribes.” (Sewell, 2001, p. 96) Today, Arabic is the

most commonly used language in Egypt.

Interestingly enough, when it comes to the development of

writing, some historians developed a different theory regarding the creation of

Egyptian art and the hieroglyph and communication in linguistics. It is

suggested that “…Egyptians may not actually have adopted the system of writing

already in use in Mesopotamia; rather they only borrowed the idea of writing.” (Silverman,

2011, p. 204)

Akhenaten, the ruler pictured in the stele “Akhenaten and His Family” (Stokstad & Cothren, 2014, p. 71) , “altered the style

and grammar of classical language [and] introduced a new style of art and

architecture.” (Silverman, 2011, p. 204) The theory is that

during his reign, Akhenaten also created and developed written language in

Egypt.

Akhenaten,

along with his wife, Nefertiti, ruled from 1352-1336 BC. In the limestone

relief, “Akhenaten and His Family”, hieroglyph is combined with a new kind of

stylized relief carving. The image depicts both Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their

three children in a state of relaxation and play. A striking departure from the

highly mathematical depictions seen in earlier carvings is revealed. There is a

level of emotion conveyed in this carving, as opposed to the stoic figures that

were the norm. Hieroglyph is used to not only to relate the scene linguistically,

but symbolically as well, as seen in the ankhs that are splayed to indicate the

showering of eternal life upon the rulers. The ankh, a symbol of life, could

also be used to imply good fortune or good crops, depending on the “internal

details…added to the circular section…the circle resemb[ling] a woven braid…a twisted

shape made from plant stems around harvest time, intended to bring good fortune” (Kemp, 2005,

p. 9)

The sun, representing the sun god Aten dispenses this life and fortune.

Akhenaten

was responsible for the shift in religion from the polytheistic to the

monotheistic while he was in power, and even changed his name to represent this

change. It could be argued that the decision was made not out of religious

obligation, but out of political and power aspirations. Akhenaten, whose

previous name had been Amenhotep, had been born into the cult that worshipped

the god Amun. However, “[b]y the time of Amenhotep IV, the Cult of Amun owned

more land than the king.” (Mark, 2014) It would make sense,

that as a political figure, Amenhotep would”…[outlaw] the old religion and [proclaim]

himself the living incarnation of a single, all-powerful, deity known as Aten” (Mark, 2014) thus he

abolished all worship of other gods, and closed the temples and places of

worship that would subscribe to any of the other cults. This would transfer all

the land and power previously held by those who followed Amun, to himself. When

these political aspirations are known, it changes the meaning of the Stele of

Akhenaten. No longer viewed as an artwork that promotes the sanctity of the

royal family, it now indicates a particularly dangerous degree of political

influence. While the symbols used represent a bestowing of life, the history

indicates a ruler who removes certain freedoms from the population in order to

gain power.

The

use of hieroglyph in political statements of art, is still used today. Over the

past several decades, there has been a wave of political unrest in Egypt,

resulting in what is often a military state, as well as the civil reactions to

this upheaval. Street art has become a way of communicating these changes to

the general public, and serves as a reminder of the past atrocities that have

happened as a result of a government that, like Akhenaten, attempts to supress

freedom of speech and worship.

Soraya

Morayef, a freelance London based journalist, has been tracking and writing

about Egyptian Street art for several years. She has, over time, built a sense

of trust with the artists. At one point, the majority of street art was created

at night, with fears of arrest hanging over the heads of the artists. Now, more

and more works are being completed during the day, although the artists are

still subject to much scrutiny and some public backlash.

The designer Ganzeer, (a pseudonym), is one of

the artists who found that his work was not considered acceptable among

government ranks. Now residing in the United States of America, Ganzeer left

Egypt before he became sought after by the police and military. He maintains

that his decision to leave was not politically motivated, however, by the time

that he left the country, he was already being decried by public media as a

menace to society due to the nature of his work (Pollack,

2014) .

His use of hieroglyph is seen in several of his works, but is prominently

displayed in the mural “Foundations” which was created on a large wall in

Adilya, Bahrain.

Depicting

a bird’s head on a human body, and shrouded in a yellow shawl decorated with

hieroglyphic images, the piece is a statement of “the many minority cultures in

Bahrain and their involvement in, not only building the country, but also in

shaping Bahraini identity” (Ganzeer, 2014) . The hieroglyphics on

the yellow band of the robe “are based on folkloric visuals from a multitude of

minority cultures existing in Bahrain and more or less reserved to the worker

populations in the country, such as Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Filipino

and Thai” (Ganzeer, 2014) . There is an odd

reversal of image in the mural, as the Egyptian hieroglyphic symbol of a bird

with a human head indicates the word ‘soul’, suggesting that “the inner self

most closely resembled the outward, physical person” (Kemp, 2005,

p. 179)

Ganzeer’s interpretation, when compared with the multicultural aspect of the

piece, indicates a link between the state of the people and the state of soul, with

the soul resembling the amalgamation of several cultures, and the peace of the

acceptance of such. The inclusion of ideograms from several cultures also

indicates the feeling of inclusion and a celebration of the differences within

Bahrain’s culture.

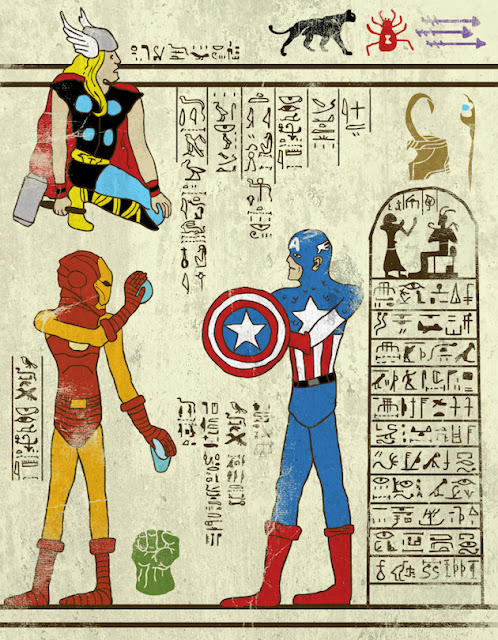

Pop

culture has also contributed widely to the current use of hieroglyphs. From

tattoos to the use of hieroglyph in storytelling, North American culture uses

the same images, adhering to interpretation while using them for symbolism and

fashion. On the other hand, artists such as Josh Lane, an American artist, has

provided a new platform for the hieroglyph. His series, “Hero-glyphs” uses

hieroglyph to recount the popular stories seen in comic books. Lane’s personal

interest in the Ancient Egyptian culture led to the study of hieroglyph, which

he uses in place of English. He also takes his art one step further by mimicking

the grid based body types seen in Egyptian art. (Butler, 2014)

Given

the wide range of use, as well as the fact that the culture that created the

hieroglyph no longer exists, is has been questioned as to whether or not appropriation

of the hieroglyph is considered to be a threat. According to one internet

blogger, the fear of appropriation no longer exists due to the fact that

hieroglyph is no longer used in daily Egyptian language and Ancient Egyptian

culture is no longer in use. Arabic is now the most commonly used language in

Eqypt. However, some would disagree, citing the fact that hieroglyph is often

misrepresented and that pop culture does not necessarily serve to education the

population, but to entertain it. The discussion surrounding appropriation of Egyptian

art has been primarily focused on the artifacts that have been relocated over

centuries to other countries, and those countries refusal to give the artifacts

back to Egypt. At the same time, there are those who believe that the use of

hieroglyph in tattoo form misuses the symbolic meaning of the word, siting a

lack of education on the part of the end user.

Hieroglyph

has continued to be a source of fascination for both artists and scholars.

There is, to some degree, a sense of mystery that still surrounds the ancient

Egyptians and their forms of communication and art. Because there are no

original speakers of the language, it remains unknown if interpretations by

historians are correct, and much of the pronunciation has been lost and

therefore left to conjecture. Still, it is heartening to see hieroglyphic

imagery continue to be used in art and to witness the impact that it still has on

a population, regardless of its use in political spheres or popular culture.

References

Butler, A. (2014, January 10). Hero-Glyphics

by Josh Lane. Retrieved from DesignBoom:

http://www.designboom.com/art/hero-glyphics-by-josh-lane-01-10-2014/

Ganzeer. (2014, February 25). Foundations Mural. Retrieved from

Ganzeer:

http://www.ganzeer.com/post/79255967646/project-foundations-mural-more

Kemp, B. (2005). 100 Hieroglyphs Think Like an Egyptian. New

York: Penguin Group.

Malek, J. (2003). Egypt 4000 Years of Art. New York: Phaidon

Press Limited.

Mark, J. J. (2014, April 17). Akhenaten. Retrieved from Ancient

History Encyclopedia: http://www.ancient.eu/Akhenaten/

Pollack, B. (2014, July 10). Hieroglyphics that won't be Silenced.

Retrieved from New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/13/arts/design/ganzeer-takes-protest-art-beyond-egypt.html?_r=0

Sewell, B. (2001). The Accomplishments of Ancient Egyptian Civilization.

In B. Stalcup, Ancient Egyptian Civilization (pp. 95-98). San Diego:

Greenhaven Press Inc.

Silverman, D. P. (2011). Text and Image and the Origin of Writing in

Ancient Egypt. In D. C. Patch, Dawn of Egyptian Art (pp. 203-209). New

York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Stokstad, M., & Cothren, M. W. (2014). Art History 5th Ed,.

New York: Pearson.

The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy. (2014, October 31). Interview

With Ganzeer. Retrieved November 21, 2015, from The Tahrir Institute for

Middle East Policy: http://timep.org/commentary/interview-ganzeer/